We face another year of pandemic Passover. Most congregations are still shuttered, and Pesach worship will be remote and online. Seders will be small or socially distanced, a far cry from our usual crowded, joyous gatherings. Nevertheless, we will still sing Hallel, our liturgy of praises, as part of the Haggadah.

Hallel (praise), Psalms 113 to 118, is sung or recited in the synagogue on all festivals (including intermediate days), as well as on Rosh Chodesh (the first day of a new month), on all eight days of Chanukah, and, in recent years, on Yom HaAtzma-ut (Israel’s Independence Day). Hallel is also recited on the eve of Pesach during the seder.1

On these sacred days of communal rejoicing, we are asked to set aside our sorrows to praise God. But how do we sing God’s praises during a time of catastrophe or pandemic? How do we sing God’s praises after a profound personal loss?

Depending on personal practice—what one chooses to include in the seder, how often one goes to services, whether an individual participates in two seder nights, and how many days are observed—Hallel can be recited as many as ten times during the festival period.

This raised a hard question for me as a liturgist. How can we sing God’s praises fully as we move into the second year of COVID-induced, socially distanced Passover seders? Could I find a liturgical response? Personally, I know how difficult this can be. My wife passed away the Shabbat before Passover twelve years ago, and the shivah ended abruptly after only two days.

I began by rereading all my prayers written about COVID and came across a line in a piece called “These Vows: A COVID Kol Nidre.” A line from it reads: “How I wish to sing in the key of Lamentations.” From there, the idea for “Hallel in a Minor Key” was born.

As I started writing, it became important to me to create a liturgy that was robust enough to stand as a full alternative Hallel, reflecting praise in the midst of heartbreak and sorrow. To me, this meant two things. First, I wanted to make sure that each psalm in the classic Hallel was represented by at least one Hebrew line in this liturgy. Second, I wanted to include the sections for waving the lulav in this liturgy, to ensure that it could be used on Sukkot by those with that practice.

Still, something was missing—music specific to this liturgy. Song is a vital part of the public recitation of Hallel, and it serves to create a personal connection with prayer. So, I adapted the opening poem into lyrics—carrying the same name as the entire liturgy—and began searching for someone to compose the music. I listened to a lot of Jewish music online, starting with my small circle of musician friends. When I heard Sue Radner Horowitz’s Pitchu Li, my search for a musician was over.

“Hallel in a Minor Key” begins in minor, but mid-chorus, with words of hope, it switches to a major key. In discussing the music, we both felt it was important to follow the tradition of ending even the most difficult texts with notes of hopefulness. Indeed, the shift reflects our prayer that sorrows can be the doorway to greater love, peace, and—eventually—to growth, healing, and joy.

We also talked about drawing on Eichah trope—used to chant Lamentations on Tishah B’Av, as well as the haftarah on that day—as a musical influence. This idea follows the tradition of bringing Eichah trope into other texts as a sort of musical punctuation. Many will recall its use in M’gillat Esther on Purim. Eichah trope is also traditionally used during the chanting of Deuteronomy 1:12, as well as in selected lines from the associated haftarah for Parashat D’varim, Isaiah 1:1–27. Sue wove hints of “the trope of Lamentations” into the chorus melody of “Hallel in a Minor Key.”

A PDF of the liturgy, including sheet music, can be downloaded here. You can hear a recording of the music here. Sue’s rendition of Pitchu Li, written prior to this liturgy, is also included as part of “Hallel in a Minor Key.” That music can be found on her album Eleven Doors Open.

This is our gift to the Jewish world for all the many blessings you have bestowed upon us. We offer it with a blessing. We encourage you to add music or additional readings that would add meaning to your worship. If you use the liturgy in your worship, we’d love to hear from you. You may reach Alden at asolovy545@gmail.com and Sue at srrhorowitz@gmail.com.

Portions of “Hallel in a Minor Key” were first presented during a Ritualwell online event, “Refuah Shleimah: A Healing Ritual Marking a Year of Pandemic.” Portions were also shared in a workshop session at the 2021 CCAR Convention, held online.

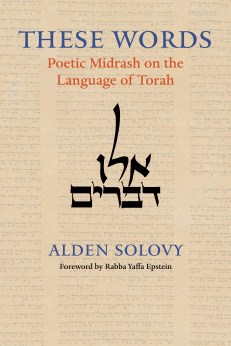

Alden Solovy is a liturgist based in Jerusalem. His books include This Grateful Heart: Psalms and Prayers for a New Day, This Joyous Soul: A New Voice for Ancient Yearnings, and This Precious Life: Encountering the Divine with Poetry and Prayer, all published by CCAR Press.

1 Rabbi Richard Sarason PhD, Divrei Mishkan T’Filah: Delving into the Siddur (CCAR Press, 2018), 190.